Asylum Seekers, Migrants and Illegal Immigrants:

How the British Media Reported the 2015 European Refugee Crisis

A Research Paper

By Paul McBride

30th November 2015

ABSTRACT

British mass media has represented refugees with a range of terms and labels; some fair and accurate, others not. Correct application of the words ‘refugee’ and ‘migrant’ is important, as a refugee is someone forced to flee conflict or persecution, whereas a migrant is someone who moves from one place to another for better work or living conditions. This paper examines British mass media’s representation of refugees during the European refugee crisis of 2015, to investigate whether news outlets potentially contributed to the demonization and marginalisation of refugees in the receiving country. Results showed a news outlet from the left of the political spectrum to be largely sympathetic to refugees, and news outlets from the centre and right to be largely unsympathetic to refugees. Each news outlet had clear and obvious agendas in how they framed their refugee stories. There is potential for audiences to view refugees in a negative light as a result of a majority of stories examined.

KEY WORDS: refugee, asylum seeker, migrant, refugee crisis, Syria, agenda-setting, media framing, mass media, media audiences

INTRODUCTION

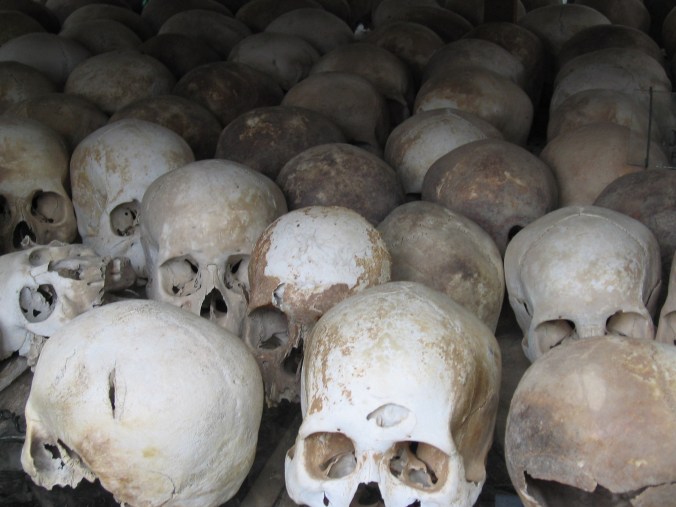

In 2015, it is estimated that global refugee numbers exceeded 50 million people for the first time since World War II (UN Refugee Agency, online). While much of Western media seeks to portray refugees as an unstoppable human tidal wave bringing instability and cultural decline to overwhelmed receiving countries, refugees make up only a little more than half of one percent of the global population. Stories on refugees traditionally polarise public opinion, but a near-universal public outpouring of sympathy occurred when the story of Aylan Kurdi, a three year-old Syrian boy whose body washed up on a Turkish beach, broke on September 2nd.

It has been suggested by communications scholars that mass media only reinforces existing beliefs (Ross and Nightingale, 2003, p.100) without playing a part in creating them, and this paper will test that theory. By studying three British media outlets’ coverage of the Syrian refugee crisis during the month of September 2015, beginning at the time of Aylan Kurdi story, conclusions will be drawn concerning the extent to which the British media’s coverage was balanced and informative, whether were refugees represented fairly and accurately, and if any evidence of framing or agenda-setting existed.

AGENDA SETTING AND FRAMING IN THE REFUGEE SPHERE

More than five centuries after the printing press was introduced to Western audiences (Eisenstein, 1980, p.3), the first mass media agenda-setting theory was formally developed by McCombs and Shaw with their seminal 1972 work ‘The Agenda-Setting Function of Mass Media’ in Public Opinion Quarterly. By conducting a study on audiences in the 1968 American presidential election, they were able to show a strong correlation between the importance placed on an issue by mass media and the perception of the issue by the audience (1972, p.178). This ground-breaking work has since been expanded on, including by Rogers and Dearing (1988, p.555), who described the connection between the media’s, the public’s and public policy agendas as being tightly intertwined.

Media framing is a subject closely linked to agenda-setting. It was concisely described by Entman (1993, p.52) as “select[ing] some aspects of a perceived reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text, in such a way as to promote a particular problem definition, causal interpretation, moral evaluation, and/or treatment recommendation”. In 1999, American communications professor Dietram Scheufele wrote an extensive article on the subject entitled ‘Framing as a theory of media effects’ in Journal of Communication. In this work he clarified and defined the subject of media framing in terms of how it relates to agenda-setting, and went even further than many works on agenda-setting by analysing how a subject presented to an audience (‘the frame’) can influence the actions and choices they make using that information (1999, pp.114). Similar to McCombs & Shaw (1972), this text and Entman’s description provide appropriate definitions, rationale and examples of framing and agenda-setting, to be used in the research design and analysis of findings for this research paper.

Britain’s cultural makeup has constantly evolved for thousands of years, with incoming groups receiving varying degrees of welcome, depending on circumstances. A contemporary watershed moment was reached with the introduction of the Commonwealth Immigration Act in 1962, which dramatically provided opportunities to British subjects globally (Cesarani, 1996, p.65), although it also brought opposition in the form of the racist rhetoric of Powellism (Buettner, 2014, p.710). A range of terms for labelling immigrants and refugees followed, with status determination and labels “infusing the world of refugees” (Zetter, 1991, p.39). Quickly, the problem rose of immigrants and refugees viewing their identity in very different terms to those bestowing the labels (Harrell-Bond, 1986, p.15).

Much has been written about the wide variety of negative connotations of refugees used by mass media and the likely effects on audiences. Philo and Beattie (1999, p.171) described how coverage of refugees in British media uses disaster terminology, presenting the receiving nation as being victim to ‘floods’ and ‘tidal waves’. Van Dijk (2000, p.33) explained how Western media consistently described refugees as a threat, Lynn and Lea’s (2003, p.425) analysis of readers’ letters to newspapers showed that ‘asylum seeker’ is “more often taken to mean ‘bogus asylum seeker’”, whereas Goodman (2007, p.35) argued that there is a tendency in Western media to liken the movement of refugees to animals breeding. A study by Kaye (2001, p.53) showed that traditionally right-wing newspapers are more likely to label asylum-seekers as making bogus claims or as ‘economic migrants’. O’Doherty and Lecouteur (2007, p.1) analysed the social categorisations and marginalising practices applied to asylum seekers in the media, arguing that certain terms, when used by mass media, including ‘illegal immigrants’ and ‘boat people’, encouraged marginalising practices resulting in social isolation and fear. Leudar et al (2008, p.187) took an interesting approach to the subject, by using a collection of global refugee experiences to analyse hostility displayed towards asylum seekers in the British media and the social and psychological effects arising as a result. They found the majority of asylum seekers in Britain formed their new personal identity around the hostility they experienced in the media and many suffered psychological problems as a result. Innes (2010, p.456) explains how, in Britain, asylum seekers, despite being some of the most vulnerable people in the world, are constructed in the media as a “homogeneous collective that threatens the nation’s interests”, and how government policy has been complicit in supporting this approach, which links back to Rogers and Dearing’s (1988, p.555) view that the media and public policy have tightly-linked agendas. By looking at marginalising practices used by media and the real-life results, existing studies have described the harmful consequences for refugees already living in an environment of immense stress and fear.

Many studies on the British media’s treatment of refugees are either fairly general or lacking specificity (King and Wood, 2013, p.55). This work will fill that gap by concentrating on how refugees are portrayed in stories produced by a set number of publications across the left-right political spectrum during a time period of just the month of September 2015: a time when the 2015 European refugee crisis saturated mass media following widespread publication of pictures of drowned Syrian three year-old, Aylan Kurdi. The only similar work is that of Majid Khosravinik (2010, p.18), who conducted a critical discourse analysis on British newspapers’ strategies towards representing asylum seekers between 1996 and 2006, taking into account traditional ideological stances on the political spectrum, concluding that all newspapers represent asylum seekers similarly. This is a useful study for academic comparison, but this work narrows the focus and provides a more current analysis of the subject.

METHODOLOGY

While the subjects of agenda-setting, media framing and the representation of refugees in the media have studied in a general sense or in a particular nation, this work goes further by examining the approaches used by a selected group of publications over a designated time period, and bringing research in this area into the contemporary sphere while doing so. By doing so, it answers the question: to what extent has the British media’s coverage of the European refugee crisis in September 2015 been balanced and informative, and were refugees represented fairly and accurately as a result? It also examines the extent to which British media outlets’ traditional political alignments affected the way they covered the refugee crisis, did media outlets cover the refugee crisis and describe refugees more sympathetically than others, was there any evidence of framing or agenda-setting by British media in this period, and to what extent did the differing terminology used by media outlets in this period have the potential to contribute to the demonization of refugees.

From the 1st to 30th September 2015, stories on the European refugee crisis were collected from news sections of The Guardian, Daily Mail, and the BBC. These publications were chosen for review as they provide a range of political alignments on the left-right spectrum. The Guardian, since its inception in Manchester in 1821, has traditionally been a left-wing or centre-left publication, and has been known for refugee advocacy (Pupavac, 2008, p.270). The Daily Mail, since its 1896 creation, has been considered a conservative or right-wing publication, and has received criticism for portraying refugees in an unfair light (Khosravinik, 2009, p.477). The BBC, however, is bound by its charter to be impartial in all matters (BBC Editorial Guidelines, online), so theoretically should report news from a neutral position at all times.

Refugee stories were brought together in a Microsoft Excel spreadsheet, sorted by publication and date. Around thirty stories were collected from each news outlet, from a range of dates and editions over the month of September. The stories were compiled and the journalists’ use of language examined, with particular focus on the use and frequency of the terms ‘migrant’, ‘refugee’, ‘asylum seeker’ and ‘illegal immigrant’, and whether the use of any of these terms was consistent throughout each of the news outlets. The stories were also examined for use of other forms of language which may portray refugees in a negative light, and whether the use of language matched the traditional political stance on refugees of each news outlet. Suggested limitations of the research method include the small range of news outlets examined, and the restricted period of time in which to examine stories produced. As with any study, a larger sample may produce a more accurate mean result.

FINDINGS

On September 2nd, the story of Aylan Kurdi broke, and The Guardian dedicated more than ten stories to the subject over the next 24 hours. The first ran on September 2nd (The Guardian, World News, online) with the headline ‘Shocking images of drowned Syrian boy show tragic plight of refugees’ and follow-up stories included those with headlines ‘Family of Syrian boy washed up on beach were trying to reach Canada’, ‘Aylan Kurdi: friends and family fill in gaps behind harrowing images’, ‘Will the image of a lifeless boy on a beach change the refugee debate?’, ‘Refugee crisis: what can you do to help?’, ‘Aylan Kurdi: funeral held for Syrian boy who drowned off Turkey’, ‘Syrian refugee crisis: why has it become so bad?’ and ‘Refugee crisis: “Love the stranger because you were once strangers” calls us now’ (The Guardian, World News, online). These initial stories used language which was sympathetic to refugees, contained no derogatory words or phrases, and described the trials they faced with words like ‘harrowing’ and ‘brutal’, while also describing in detail the extreme dangers refugees face making the journey across the Mediterranean Sea. The word ‘migrants’ did not appear in any of these stories; instead, ‘refugee’ or ‘asylum seeker’ were used, or, in more than 50% of cases, simply ‘family’, ‘Syrians’ or ‘people’ (The Guardian, World News, online).

By September 10th, the Aylan Kurdi story was no longer being covered by The Guardian, but coverage switched to the refugee crisis in a broader sense. Over the following ten days, stories with the headlines ‘Refugee crisis: Juncker calls for radical overhaul of EU immigration policies’, ‘Refugee crisis: “Europe needs to take big numbers. Until then, chaos reigns”’, ‘Refugee crisis: we must act together, says Merkel ahead of emergency summit’ and ‘Refugee crisis: Giving Europe the chance to evolve’ appeared (The Guardian, World News, online). The words ‘refugee’ and ‘asylum seeker’ were still used to describe Syrians crossing the sea by boat in all cases (The Guardian, World News, online), and the news outlet’s editorial policy was still one of portraying the plight on asylum seekers in a sympathetic light, particularly in its scathing article on the Hungarian President’s, among others’, apathy regarding the situation (The Guardian, World News, online).

During the last ten days of September the word ‘migrant’ appeared in two stories: ‘Refugee crisis: EU splits exposed at emergency summit – as it happened’ and ‘EU refugee crisis “tip of the iceberg”, says UN agency’ (The Guardian, World News, online). However, during this time The Guardian published an article criticising the Daily Mail’s representation of refugees, entitled ‘Three problems with the Daily Mail’s story about Syrian refugees’, in which the Daily Mail’s claims about number of refugees, validity of asylum claims, and country of origin of the majority of refugees are strongly refuted (The Guardian, World News, online).

On September 2nd, as the Aylan Kurdi story broke, the Daily Mail’s initial response was to run a story with the headline ‘Migrant crisis shows the EU at its worst’ (Daily Mail, Debate Homepage, online). The story referred to ‘lifeless migrant children’ and placed blame for the lack of a solution to the situation away from British Prime Minister, David Cameron, to German Chancellor Angela Merkel. A series of stories followed with the headlines ‘The final journey of tragic little boys washed up on a Turkish beach’, ‘God be with you, little angel: The world shows its grief and anger over the death of tragic Syrian toddler Aylan’, ‘”Breathe, breathe, I don’t want you to die!”: Father of Aylan Kurdi relives the terrible moments he tried to save his two sons but they died in his arms’, and ‘Tragic Aylan’s final journey’ (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). These stories referred to the tragedy using sympathetic language, and used the word ‘refugee’ or, quite simply, ‘families’ instead of ‘migrant’.

By September 6th, editorial policy changed, and in the vast majority of stories for the rest of the month, refugees were referred to as migrants. In a story with the headline ‘Britain wants to quit Europe: Shock new poll shows EU “no” camp ahead for the first time as Cameron prepares to face down Tory rebels’, the journalist referred to the ‘migrant crisis engulfing the continent’, using a synonym of inundate/flood/deluge to describe refugee movement (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). Continuing use of the word ‘migrant’ in place of ‘refugee’ occurred on September 7th in a story with the headline ‘The image of Syrian toddler Aylan, three, washed up dead on a Turkish shoreline has shocked the world – but he is not the only child victim of the migrant crisis’, while on September 8th, a story with the headline ‘Aylan’s father just wanted better dental treatment: Liberal Senator Cory Bernardi’s brutal claim that drowned Syrian boy wasn’t a “real refugee”’ correctly labelled them as refugees despite the message of the story (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). From September 10th, the Daily Mail exclusively used the word ‘migrant’ in place of ‘refugee’ or ‘asylum seeker’ without exception, and on September 11th, the validity of Aylan Kurdi’s father’s story was called into question in a story with the headline ‘Father of Aylan Kurdi angrily hits out at Iraqi mother who accused him of being a people smuggler’ (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online).

By September 23rd, all refugee stories were moved to a section of the website labelled ‘Immigration’ (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). In stories with the headlines ‘Migrant crisis proves Britain’s case for EU reform’, ‘Rape and child abuse are rife in German refugee camps’ and ‘Police clear migrant camp between Italy and France and accuse them of using electricity and water without paying for it’, refugees are described as seeking ‘job opportunities and better social care’ as the authorities attempt to ‘stem the tide of migrants’ (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online).

From September 3rd, the BBC ran all stories on refugees under the banner ‘Migrant Crisis: _____’, such as ‘Migrant Crisis: Photo of drowned boy sparks outcry’ and ‘Migrant crisis: Drowned boy’s father speaks of heartbreak’ on September 3rd, and ‘Migrant crisis: Why the Gulf states are not letting Syrians in’ on the 7th (BBC, World News, online). In a September 3rd story with the headline ‘Migrant Crisis: Canada denies Alan Kurdi’s family applied for asylum’ (BBC, World News, online), refugees were consistently referred to as ‘migrants’ while it was simultaneously acknowledged military attacks forced them to flee.

On September 9th, an online petition was created under the banner ‘Request BBC use the correct term Refugee Crisis instead of Migrant Crisis’ (Change.org, online), which quickly gained 30,000 signatures (the figure had reached 73,000 at the time of writing). The same day, the BBC published a story with the headline ‘Migrant crisis: How Middle East wars fuel the problem’, in which the journalists included the words “”The new crisis is about refugees” and “Some Western politicians, and journalists, are taking proper notice for the first time of a refugee crisis” (BBC, World News, online).

On September 14th, the BBC published a story with the headline ‘Migrant crisis: What next for Germany’s asylum seekers?’ which used the words ‘asylum seekers’ in place of ‘migrants’ despite the ongoing use of the word ‘migrant’ in the headline (BBC, World News, online). For the rest of the month, the word ‘migrants’ only appeared sporadically, and was dropped from headlines. The word ‘refugee’ began to appear from September 16th, including in the stories ‘Middle East refugees who chose Brazil over Europe’ and ‘Portsmouth takes more asylum seekers than other cities’ (BBC, World News, online). By September 18th, refugee stories began with the words “Syria Refugee Crisis: _____”, such as ‘Syria refugee crisis: Yarmouk pianist’s perilous journey to Greece’ (BBC, World News, online).

DISCUSSION

On September 2nd, the story of Aylan Kurdi broke, and The Guardian published a series of articles which reported on the refugee crisis sympathetically and framed the situation in such a way to potentially provoke further thought and discussion. Matching Entman’s definition of a frame (1993, p.52) as “select[ing] some aspects of a reality and mak[ing] them more salient in a communicating text”, The Guardian deliberately reported on the situation with humanity and empathy, with little likelihood of demonization or marginalisation of refugees as a result.

This sympathetic framing continued throughout the time period studied. With stories with headlines such as ‘Shocking images of drowned Syrian boy show tragic plight of refugees’ and ‘‘Will the image of a lifeless boy on a beach change the refugee debate?’ (The Guardian, World News, online), The Guardian’s policy of reporting provided a wider frame of reference with which its audience could understand the situation, and show empathy and sympathy for refugees as a result. This is consistent with Hartmann and Husband’s (1974, p.479) description of mass media being “capable of providing frames of reference or perspective within which people become able to make sense of events” and McCombs and Shaw’s (1972, p.177) theory that mass media does not only set the public agenda on an issue, but influences “the salience of attitudes towards the issue”.

This approach is also consistent with the findings of Khosravinik’s (2010, p.488) study, which showed The Guardian, probably due to its traditionally liberal political alignment, “draws on topics of human rights, ethics, human values, usefulness and contribution in the positive representation of immigrants and refugees”. The Guardian’s policy on reporting refugees also counters King and Wood’s (2013, p.55) view that British media’s treatment of refugees is lacking specificity, with more in-depth stories like ‘Aylan Kurdi: friends and family fill in gaps behind harrowing images’ (The Guardian, World News, online). Overall, over the month of September 2015, The Guardian consistently reported on refugees fairly and accurately, displayed evidence of agenda-setting and framing which gave its audience a broader understanding of the situation, contributed only minimally to potential demonization of refugees by using almost consistently appropriate terms and categorisations, and was most likely influenced by its traditional political alignment in doing so.

The Daily Mail began September with balanced and informative reporting, before quickly changing its policy and pursuing an agenda of demonizing refugees for the rest of the month. For four days after the Aylan Kurdi story broke, the Daily Mail used language sympathetic to refugees while reporting on the crisis, resulting in a fair and accurate representation of the people involved, as well as the general situation. A shift occurred on September 6th, with the words ‘asylum seeker’ and ‘refugee’ being replaced with ‘migrant’ in all refugee stories (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). This change had the potential to contribute to the marginalisation of refugees, as is consistent with O’Doherty and Lecouteur’s (2007, p.1) study on social categorisation. By applying the same terms in monotonous fashion every day in its stories, the Daily Mail did what Scheufele (1999, p.105) describes as “media fram[ing] images of reality in a predictable and patterned way” in order to achieve a particular result; in this case the potential alienation of refugees. By choosing to place all its refugee stories in a news section of their website with the title ‘Immigration’, the Daily Mail played an important part in shaping the reality of the crisis, and – as McCombs and Shaw (1972, p.176) describe any situation in which mass media determines what is important – setting the agenda of the situation.

Choice of wording with which to describe and categorise refugees was the Daily Mail’s biggest contribution to unbalanced and inaccurate reporting during the time period studied. By using phrases such as “migrant crisis engulfing the continent” in a September 6th story (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online), the Daily Mail used what Philo and Beattie (1999, p.171) describe as disaster terminology; words which have the potential to alienate and marginalise refugees. In the last week of the month, the Daily Mail turned to reporting stories about rape and child abuse in refugee camps, refugees allegedly stealing water and electricity, and refugees allegedly “seeking job opportunities and better social care” (Daily Mail, News Homepage, online). This is consistent with Van Dijk’s (2000, p.33) description of Western media consistently describing refugees as a threat and as being associated with crime, and is likely to bring about the type of result confirmed by Lynn and Lea’s (2003, p.425) analysis of readers’ letters to newspapers, which showed that ‘asylum seeker’ is more often taken to mean ‘bogus asylum seeker’. This also matches Kaye’s (2001, p.53) study which showed that traditionally right-wing newspapers are more likely to label asylum-seekers as ‘economic migrants’. Overall, over the month of September 2015, the Daily Mail consistently did not report on refugees fairly, displayed evidence of agenda-setting and framing, potentially demonized and marginalised refugees through poor choice of language and social categorisation, and was most likely influenced by its traditional political alignment in doing so.

In a mirror image of the Daily Mail’s reporting on the crisis, the BBC began September reporting on refugees inaccurately and with incorrect categorisation, before improving as the month progressed. By headlining all refugee stories with ‘Migrant Crisis: _____’ (BBC, World News, online), the BBC, despite its charter binding it to neutrality, showed evidence of agenda-setting to inaccurately represent refugees. This is consistent with McCombs and Shaw’s (1972, p.178) description of how the agenda of a news outlet is determined by its “pattern of coverage on issues over some period of time”. By framing the mass movement of people as economic migration instead of people fleeing conflict, the BBC not only potentially breached its charter, but also seemingly confirms Dearing’s (1988, p.555) view that the media and public policy have tightly-linked agendas (for the 12 months up to June 2015, the UK accepted only 166 Syrian refugees under the government’s ‘vulnerable persons’ initiative (Eurostat, online)). By framing refugees in this way, the BBC potentially contributed to its audience being more likely to consider refugees as economic migrants. This is consistent with Scheufele’s (1999, p.106) definition of a media frame as being “largely unspoken and unacknowledged” and something that “organize[s] the world for [those of] us who rely on their reports”.

The improvement in the BBC’s fairness and accuracy of reporting may have been affected by an online petition on September 9th challenging it to use more appropriate terminology (Change.org, online). Overall, over the month of September 2015, the BBC reported on refugees with inconsistent levels of fairness and accuracy, displayed evidence of agenda-setting and framing, potentially demonized refugees through poor choice of language and social categorisation, and potentially breached its charter in doing so.

Of the three publications studied, there was found to be unbalanced reporting, agenda-setting, framing, and the use of incorrect terminology in each, all of which had the potential to demonize refugees during September 2015. The extent to which this happened differed greatly, though. The Guardian, likely affected by its traditional political alignment, reported on the crisis with stories of which the vast majority were sympathetic, the BBC reported on the crisis with stories of which a slight majority were sympathetic, and the Daily Mail, likely influenced by its traditional political alignment, reported on the crisis with stories of which the overwhelming majority were unsympathetic.

CONCLUSION

Refugees were represented poorly by British media during the European refugee crisis of 2015, with no publication examined in this study completely blame-free. For the 30-day period examined, there was evidence of a determined agenda to dehumanise refugees and call into question their motives through incorrect social categorisation, poor choice of language and questionable framing. The likely impact of this is that refugees will face an increased number of social and psychological obstacles in their quest to make a safe and stress-free life for themselves and their families.

As refugee numbers reach an all-time high in 2015, it is vital that those who have had the good fortune and dumb luck to have been born in a war-free nation give refugees the greatest possible chance of a safe and happy life.

REFERENCES

British Broadcasting Corporation, Editorial Guidelines, BBC website, accessed 8th November 2015: http://www.bbc.co.uk/editorialguidelines/page/guidelines-impartiality-introduction

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant Crisis: Photo of drowned boy sparks outcry’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34133210

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant crisis: Drowned boy’s father speaks of heartbreak’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34143445

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant Crisis: Canada denies Alan Kurdi’s family applied for asylum’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-34142695

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant crisis: Drowned boy buried’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34143445

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant Crisis: Why the Gulf States are not letting Syrians in’, World News, online, accessed 7th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-34173139

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant crisis: How Middle East wars fuel the problem’, World News, online, accessed 9th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34193762

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘What happens when an asylum seeker arrives in Germany?’, World News, online, accessed 9th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34202394

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Migrant crisis: What next for Germany’s asylum seekers?’, World News, online, accessed 14th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34175795

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Middle East refugees who chose Brazil over Europe’, World News, online, accessed 16th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-latin-america-34264937

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Portsmouth “takes more asylum seekers than other cities”’, World News, online, accessed 17th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-hampshire-34272532

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Syria refugee crisis: Yarmouk pianist’s perilous journey to Greece’, World News, online, accessed 18th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-34255104

British Broadcasting Corporation, ‘Thirteen die in ferry collision off Turkey’, World News, online, accessed 16th September 2015: http://www.bbc.com/news/world-europe-34307745

Buettner, E, 2014. ‘This is Staffordshire not Alabama: Racial Geographies of Commonwealth Immigration in Early 1960s Britain’, The Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History, Vol. 42, No. 4, p.710.

Cesarani, D, 1996. ‘The changing character of citizenship and nationality in Britain’, Citizenship, Nationality and Migration in Europe, p.65.

Daily Mail, ‘Migrant crisis shows the EU at its worst’, Debate Homepage, accessed 5th November 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/debate/

Daily Mail, ‘The final journey of tragic little boys washed up on a Turkish beach: Mother and sons who died in sea tragedy are taken from morgue after heartbroken father says goodbye to the family he couldn’t save’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 2nd September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3219553/Terrible-fate-tiny-boy-symbolises-desperation-thousands-Body-drowned-Syrian-refugee-washed-Turkish-beach-family-tried-reach-Europe.html

Daily Mail, ‘God be with you, little angel: The world shows its grief and anger over the death of tragic Syrian toddler Aylan’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3220746/God-little-angel-world-shows-grief-anger-death-tragic-Syrian-toddler-Aylan.html

Daily Mail, ‘Breathe, breathe, I don’t want you to die!’: Father of Aylan Kurdi relives the terrible moments he tried to save his two sons but they died in his arms’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3221739/The-final-journey-tragic-little-boys-washed-Turkish-beach-Mother-sons-died-sea-tragedy-taken-morgue-heartbroken-father-says-goodbye-family-couldn-t-save.html

Daily Mail, ‘Just hours later Aylan Kurdi was dead: Last picture of toddler taking nap on Turkish beach before he drowned in his father’s arms’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3222148/Six-hours-setting-tragic-journey-claim-life-leave-lifeless-Turkish-beach-little-Aylan-sleeps-photograph-boy-alive.html

Daily Mail, ‘Tragic Aylan’s final journey: Father of drowned boys returns home to bury his wife and two sons – in the war-torn city of Kobane in which ISIS murdered ELEVEN of their family just three months ago’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3222135/Syrian-boys-Aylan-Galip-Kurdi-s-father-returns-Kobane-bury-sons-wife.html

Daily Mail, ‘Crying and accompanied by their mother, the four men accused of organising the fatal journey that claimed Aylan’s life arrive in court’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3222281/Crying-accompanied-mother-four-men-accused-organising-fatal-journey-claimed-Aylan-s-life-arrive-court.html

Daily Mail, ‘Britain wants to quit Europe: Shock new poll shows EU ‘no’ camp ahead for the first time as Cameron prepares to face down Tory rebels’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3223674/Britain-wants-quit-Europe-Shock-new-poll-shows-EU-no-camp-ahead-time-Cameron-prepares-face-Tory-rebels.html

Daily Mail, ‘The image of Syrian toddler Aylan, three, washed up dead on a Turkish shoreline has shocked the world – but he is not the only child victim of the migrant crisis’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 7th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3224090/The-image-Syrian-toddler-Aylan-three-washed-dead-Turkish-shoreline-shocked-world-not-child-victim-migrant-crisis.html

Daily Mail, ‘”Aylan’s father just wanted better dental treatment”: Liberal Senator Cory Bernardi’s brutal claim that drowned Syrian boy wasn’t a “real refugee”’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 8th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3225898/Liberal-senator-Cory-Bernardi-says-drowned-Syrian-boy-Aylan-Kurdi-wasn-t-real-refugee.html

Daily Mail, ‘Artistic tribute or tasteless stunt? Thirty people recreate death of Aylan Kurdi by laying in the sand on a Moroccan beach dressed in the same clothes as the drowned Syrian boy’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 10th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3227703/Thirty-people-recreate-death-Alyan-Kurdi-laying-sand-Moroccan-beach-dressed-clothes-drowned-Syrian-boy.html

Daily Mail, ‘Father of Aylan Kurdi angrily hits out at Iraqi mother who accused him of being a ‘people smuggler’ after she lost two children on same doomed boat trip that killed his family’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 11th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3230422/Abdullah-Kurdi-people-smuggler-migrant.html

Daily Mail, ‘Dalai Lama says ‘It’s impossible for everyone to come to Europe’ as he calls for ‘practical’ as well as ‘moral’ response to refugee crisis’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 14th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3233906/Dalai-Lama-says-s-impossible-come-Europe-calls-practical-moral-response-refugee-crisis.html

Daily Mail, ‘Migrant crisis just proves Britain’s case for EU reform: Foreign secretary says Britain is winning over Europe’s leaders’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 23rd September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3245470/Migrant-crisis-just-proves-Britain-s-case-EU-reform-Foreign-secretary-says-Britain-winning-Europe-s-leaders.html

Daily Mail, ‘Rape and child abuse are rife in German refugee camps: Unsegregated conditions blamed as women are seen as fair game in overcrowded migrant centres’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 25th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3247831/Rape-child-abuse-rife-overcrowded-asylum-centres-huge-surge-migrants-pushes-Germany-s-services-breaking-point-claim-womens-rights-groups-politicians.html

Daily Mail, ‘Give us an extra £385million! EU asks Britain for more money as it battles migrant crisis’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 30th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3254188/EU-asks-Britain-money-battles-migrant-crisis.html

Daily Mail, ‘Police clear migrant camp between Italy and France and accuse them of using electricity and water without paying for it’, Immigration News Homepage, online, accessed 30th September 2015: http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-3254778/Police-clear-migrant-camp-Italy-France-accuse-using-electricity-water-without-paying-it.html

Eisenstein, EL, 1980. The Printing Press as an Agent of Change, Volume 1, Cambridge University Press, p.3.

Entman, RM, 1993. ‘Framing: Towards clarification of a fractured paradigm’, Journal of Communication, Vol. 43, No. 4, p.52.

Eurostat: Statistics Explained, ‘Asylum Statistics’, Eurostat website, accessed 19th November 2015: http://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php/Asylum_statistics

Goodman, S, 2007. ‘Constructing Asylum Seeking Families’, Critical Approaches to

Discourse Analysis across Disciplines, Vol. 1, p.35.

The Guardian, ‘Shocking images of drowned Syrian boy show tragic plight of refugees’, World News, online, accessed 2nd September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/shocking-image-of-drowned-syrian-boy-shows-tragic-plight-of-refugees

The Guardian, ‘Family of Syrian boy washed up on beach were trying to reach Canada’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/03/refugee-crisis-syrian-boy-washed-up-on-beach-turkey-trying-to-reach-canada

The Guardian, ‘Aylan Kurdi: friends and family fill in gaps behind harrowing images’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/03/refugee-crisis-friends-and-family-fill-in-gaps-behind-harrowing-images

The Guardian, ‘Will the image of a lifeless boy on a beach change the refugee debate?’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/media/greenslade/2015/sep/03/will-the-image-of-a-lifeless-boy-on-a-beach-change-the-refugee-debate

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: what can you do to help?’, World News, online, accessed 3rd September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/03/refugee-crisis-what-can-you-do-to-help

The Guardian, ‘Britain should not take more Middle East refugees, says David Cameron’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/02/david-cameron-migration-crisis-will-not-be-solved-by-uk-taking-in-more-refugees

The Guardian, ‘Father of drowned boy Aylan Kurdi plans to return to Syria’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/03/father-drowned-boy-aylan-kurdi-return-syria

The Guardian, ‘Aylan Kurdi: funeral held for Syrian boy who drowned off Turkey’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/04/drowned-syrian-boy-aylan-kurdi-buried-in-kobani

The Guardian, ‘The Guardian view on the refugee crisis: much more must be done, and not just by the UK’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/03/the-guardian-view-on-the-refugee-crisis-much-more-must-be-done-and-not-just-by-the-uk

The Guardian, ‘Syrian refugee crisis: why has it become so bad?’, World News, online, accessed 4th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/04/syrian-refugee-crisis-why-has-it-become-so-bad

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: “Love the stranger because you were once strangers” calls us now’, World News, online, accessed 5th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/06/refugee-crisis-jonathan-sacks-humanitarian-generosity

The Guardian, ‘The Guardian view on Hungary and the refugee crisis: Orbán the awful’, World News, online, accessed 6th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/06/the-guardian-view-on-hungaryand-the-refugee-crisis-orban-the-awful

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: Juncker calls for radical overhaul of EU immigration policies’, World News, online, accessed 10th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/09/refugee-crisis-eu-executive-plans-overhaul-of-european-asylum-policies

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: Europe needs to take big numbers. Until then, chaos reigns’, World News, online, accessed 20th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/19/refugee-crisis-europe-needs-to-take-big-numbers

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: we must act together, says Merkel ahead of emergency summit’, World News, online, accessed 21st September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/21/we-must-act-together-on-refugees-says-merkel-as-eu-prepares-for-crisis-summit

The Guardian, ‘The refugee crisis gives Europe the chance to evolve’, World News, online, accessed 25th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2015/sep/25/refugee-crisis-european-union

The Guardian, ‘Refugee crisis: EU splits exposed at emergency summit – as it happened’, World News, online, accessed 25th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/live/2015/sep/24/refugee-crisis-eu-splits-exposed-at-emergency-summit-live-updates

The Guardian, ‘Europe’s refugee crisis – a visual guide’, World News, online, accessed 25th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/ng-interactive/2015/sep/18/latest-developments-in-europes-refugee-crisis-a-visual-guide

The Guardian, ‘EU refugee crisis “tip of the iceberg”, says UN agency’, World News, online, accessed 25th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/25/eu-refugee-crisis-tip-of-iceberg-unhcr

The Guardian, ‘Donald Tusk defends European response to “unprecedented” refugee crisis’, World News, online, accessed 30th September 2015: http://www.theguardian.com/world/2015/sep/29/donald-tusk-defends-european-values-united-nations

Harrell-Bond, BE, 1986. Imposing Aid: Emergency Assistance to Refugees, Oxford University Press, p.15.

Hartmann, P, & Husband, C, 1974. Racism and the Mass Media, London: DavisPoynter. p.479.

Innes, AJ, 2010. ‘When the threatened become the threat: The construction of asylum seekers in British media narratives’, International Relations, Vol. 24, No. 4, pp.456.

Kaye, R, 2001. ‘An analysis of press representation of refugees and asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom in the 1990s’, Media and Migration: Constructions of Mobility and Difference, p.53.

Khosravinik, M, 2009. ‘The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers during the Balkan conflict (1999) and the British general election (2005)’, Discourse & Society, Vol. 20, No. 4, p.477.

Khosravinik, M, 2010. ‘The representation of refugees, asylum seekers and immigrants in British newspapers: A critical discourse analysis’, Journal of Language and Politics, 9(1), pp.1-28.

King, R, & Wood, N, (Eds.), 2013. ‘Blaming the victim: an analysis of press representation of refugees and asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom’, Media and Migration: Constructions of Mobility and Difference, p.55.

Leudar, I, Hayes, J, Nekvapil, J, & Baker, JT, 2008. ‘Hostility themes in media, community and refugee narratives’, Discourse & Society, Vol. 19, No. 2, p.187.

Lynn, N & Lea, S, 2003. ‘A Phantom Menace and the New Apartheid: The Social

Construction of Asylum-seekers in the United Kingdom’, Discourse & Society, Vol. 14, p.425.

McCombs, ME, & Shaw, DL, 1972. ‘The agenda-setting function of mass media’, Public Opinion Quarterly, pp.176-187.

O’Doherty, K, & Lecouteur, A, 2007. ‘“Asylum seekers”,“boat people” and “illegal immigrants”: Social categorisation in the media’, Australian Journal of Psychology, pp.1-12: http://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/00049530600941685

Philo, G & Beattie, L, 1999. ‘Race, Migration and Media’, in G. Philo (ed.) Message

Received: Glasgow Media Group Research 1993–1998, Harlow: Longman, p.171.

Pupavac, V, 2008. ‘Refugee advocacy, traumatic representations and political disenchantment’, Government and Opposition, Vol. 43, No. 2, p.270.

Rogers, EM, & Dearing, JW, 1988. ‘Agenda-Setting Research: Where Has It Been, Where Is It Going?’, Communication Yearbook, p.555.

Ross, K and Nightingale, V, 2003. ‘The Audience as Citizen: Media, Politics and Democracy’ in Media and Audiences: New Perspectives. London: Open University Press, p.100.

Scheufele, DA, 1999. ‘Framing as a theory of media effects’, Journal of Communication, edition 49, pp.103-122.

Scheufele, D, 2000, ‘Agenda-Setting, Priming, and Framing Revisited: Another Look at Cognitive Effects of Political Communication’, Mass Communication & Society, Vol. 3, No. 2-3, pp.297-316.

The UN Refugee Agency, ‘Global forced displacement tops 50 million for first time since World War II – UNHCR Report’, online, accessed 25th November 2015: http://unhcr.org.au/unhcr/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=426:global-forced-displacement-tops-50-million-for-first-time-since-world-war-ii-unhcr-report&catid=35:news-a-media&Itemid=63

Van Dijk, TA, 2000, ‘New(s) Racism: A Discourse Analytical Approach’, in S. Cottle (ed.),

Ethnic Minorities and the Media, Buckingham: Open University Press, p.33.

Zetter, R, 1991. ‘Labelling Refugees: Forming and Transforming a Bureaucratic Identity’, Journal of Refugee Studies, Vol. 4, p.39.

Zygkostiotis, Z, 2015. ‘Request BBC use the correct term Refugee Crisis instead of Migrant Crisis’, Change.org, accessed 12th November 2015: https://www.change.org/p/request-bbc-use-the-correct-term-refugee-crisis-instead-of-migrant-crisis

<END>